Nature Restoration in a Depopulating Society

- Futoshi Nakamura

- Professor, Graduate School of Hokkaido University

As the mass media have reported, drastic aging and depopulating in Japanese society are considered likely to have impacts in a wide variety of areas including social security (such as medical services and care), pensions, tax revenues and infrastructure development. Therefore, declines in social welfare, administrative services and economic activities will be inevitable, and the future scenario seems to be pessimistic. But, should we really be pessimistic over the issue of depopulation? It is necessary for us not only to understand the present situation to allow us to talk about the future, but also for us to learn from past history in order to understand the present situation. First of all, I would like to confirm the present situation of Japan through looking back through past history and showing the changes of the forests, rivers and wetlands in Japan.

The population of Japan had increased although temporary or regional declines due to hunger, disease or war can be recognized. The overall trend was constant: 7,570,000 in 1192 (establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate), 8,180,000 in 1338 (establishment of the Muromachi Shogunate), 12,270,000 in 1603 (establishment of the Edo Shogunate), 33,330,000 in 1868 (the Meiji Restoration) and 126,930,000 in 2000 (present). In line with the dramatic population increase after the Edo Era, natural resources in Japan including forests seemed to be rather overused from about 300 years ago. It is often said that a well-balanced cyclical use of resources was achieved in the Edo Era, but, when the population was over 30,000,000, the forest resources seemed to almost have reached the limit, given that the society depended only on Japanese forests without using fossil fuels. As a mark of this, most satoyama in the paintings of the Edo Era are bald mountains with thin forests or pine forests growing on infertile land.

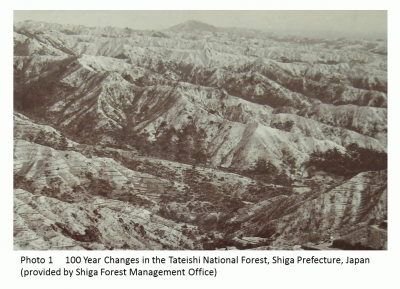

Japanese society began to use fossil fuels after the Meiji Restoration (1868), and on the other hand, it also continued to use Japanese forest resources. The Japanese forests were devastated and some mountains were mostly bald (Photo 1). Great amounts of soil brought by erosion accumulated in the rivers, and the levels of the river beds were elevated because of sedimentation. Then, floods and sediment disasters were frequently caused. During the years of high economic growth in Japan from the 1950s to 1970s, the intensification of land use progressed. In order to deal with the exponential increase in lumber demand, the Japanese government at the time promoted an “Expanding Afforestation Policy,” which cut down the natural forests mainly consisting of broadleaf trees in order to convert the forests to conifer plantations. Under the policy, artificial forests with a total area of approximately 10,000,000 ha were mostly created during this period. After that, Japanese society began to use inexpensive imported timbers, and the artificial forests in Japan were eventually preserved. Still, Japan depends on imported timbers (about 25 % self-sufficiency rate).

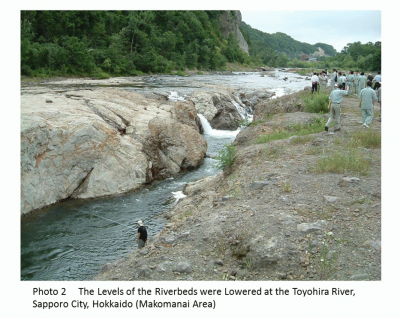

From the Meiji Era to after World War II, erosion frequently occurred at the devastated forests, and the levels of the river beds became elevated. The Government had problems of river basin management, and policies of forest conservation and sabo (erosion and sediment control) dam construction were promoted. As a result, dams were constructed on most mountain streams throughout Japan. In addition, storage dams were constructed in order to deal with electric power development and the water use necessary for high economic growth. After that, large-scale multi-purpose dams, which also have the function of flood control, became the most common method. Following this, large-scale gravel extraction was frequently conducted at rivers in order to use the gravel as a construction material for improving social infrastructure such as roads, railways and buildings. At the same time, river modification was conducted and cut-off channels were constructed for river basin management and agricultural land development.

In the Meiji Era, there were backmarshes on both riverbanks, but they decreased drastically due to river and agricultural land development plans. In Hokkaido, where the wetlands are most widely (approximately 85%) distributed in Japan, wetlands have been decreased to 60% of their Meiji Era levels since the high economic growth period, and similar decreases are also recognized in other regions of Japan. Especially, backmarsh development was progressed after the enactment of the Agricultural Basic Act in 1961, and the development of backmarshes was accelerated along with the construction of cut-off channels and embankments. In general, the levels of riverbeds have been lowered by the construction of cut-off channels as such construction to shorten the stream lengths and steepen the river bed gradients. In line with these, the groundwater levels of backmarshes has also been lowered, and the land has become available for use as farmland.

In this way, the natural environment has changed in Japan. On the other hand, the population of Japan has decreased since 2005. The population of Hokkaido has more drastically decreased than that of the main island of Honshu. The population of the eastern and northern parts of Hokkaido will decrease about 40% from 2005 to 2035, and the population size is estimated to go back to that of the early 1950s. As mentioned above, Japanese have experienced expanding local societies, but so far have never experienced shrinking societies. It will be first time for us to experience depopulating societies. Also, regime shift (when an ecological threshold has been passed, and the ecosystem may no longer be able to return to its previous state) of forests and rivers is occurring along with the change in social regime, the depopulation.

As a result of inexpensive timber imports, abandoned artificial forests are increasing throughout Japan. The forest industry is no longer profitable, and these artificial forests are becoming darker and denser as forest thinning has not been conducted. Therefore, the collapse of forest stand by typhoons is a serious concern. Depopulation and aging are progressing in the farming and mountain village areas, and the areas ever called satoyama now have mostly become marginal villages. Invading bamboo is growing massively in various places in the artificial abandoned forests. Bamboo is growing rampantly in such unmanaged forests, and collapsed dense bamboo forests are found in many places. In addition, damage by wild animals is emerging along with the human withdrawal from satoyama. Destruction of vegetation by Japanese shika deer is occurring throughout Japan. Damage caused by wild boars, monkeys and bears has also been reported. In order to restore the ecosystem that is deteriorating due to the abandoned forests, it is necessary to control timber imports and to promote the use of the artificial forests in Japan. It is an international responsibility for Japan to continuously use domestic resources as Japan has had a great impact on biodiversity in foreign countries.

In alluvial rivers in Japan, the levels of the river beds have been abnormally lowered as the river inflow volume and soil erosion have been controlled in line with the gravel extraction, dam construction and the decrease of bald mountains (Photo 2). With this, trees are growing rampantly and invading into riverbanks ever covered with gravel. Also, trees including bamboo grasses are growing massively in wetlands due to groundwater drawdown along with the inflow of soils and nutrients from surrounding watersheds. In the Kushiro Shitsugen wetlands, 60km2 of the surface areas of low-moors have decreased since 1950 due to the massive growth of Japanese alder forests.

I feel the powerlessness of humans when thinking about the restoration of nature under the great regime shifts of the ecosystem. However, nature has innate powers of recovery of the inherent ecosystem, “resilience.” For example, we can see the changes in the abandoned farmlands. The surface areas of abandoned farmlands were more than 10,000 ha in Hokkaido in the end of 2011. The abandoned farmlands which were converted from backmarshes are now returned to wetlands due to the malfunctioning of open/closed ditches. Also, abandoned forests on gentle mountain slopes adjacent to the forests are transited to secondary forests when seeds are provided from the surroundings. These are exactly in line with the passive restoration of nature.

On the other hand, the frequency of torrential rains and large-scale typhoons has increased under the influence of the global warming. Under the “National Resilience Plan (*),” the Japanese Government is going to construct embankments 10 meters in height and 300 km in total length in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake. However, I cannot help thinking that the construction of embankments is an extension of the ideas which were made during the high economic growth period. A new perspective is missing. As described in “Gezan no Shiso (in Japanese, Thoughts of Going Down a Mountain)” by Hiroyuki Itsuki, a Japanese writer, what was unseen when climbing up the mountain (the population growing period, in this essay) can be seen as a calm sight when going down the mountain (the depopulation period). Through depopulation, we may be able to find new values and possibilities that were unseen when we only aimed at material richness during the high economic growth period. It is high time for us to examine the future of disaster prevention and nature restoration in Japan, focusing on great changes in natural and social systems.

*”The National Resilience Plan” is a set of national disaster prevention plans decided by the cabinet after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Although the Japanese Government uses the word “resilience,” the reality is a set of disaster prevention plans for constructing hard, concrete structures aiming to protect human lives and properties, and very weak in considering and utilizing ecological resilience.

In a drastically depopulating society, it will be more difficult to maintain not only farmlands but also infrastructure including hospitals, schools, waterworks and roads. It is clearly impossible to continue public investment based on the present living areas, and we have to intensify land use. If human withdrawal from flooding areas becomes possible by making the best use of the land use changes, the areas will become nature restoration areas conserving fugitive species (a species adapted to colonize newly disturbed habitats) that are drastically disappearing. And at the same time, the areas would play a disaster preventive role as buffer zones corresponding to the increase of large-scale flooding along with global warming. This represents a perceptional change from gray infrastructure to green infrastructure.

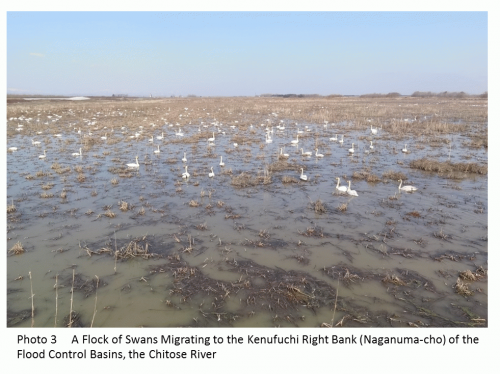

Here is an example. In order to control floods, 6 large-scale flood control basins with areas of 150-280 ha were constructed in the Chitose River watersheds in Hokkaido. These flood control basins, playing a disaster preventive role, also feature a wonderful landscape of wetlands, and many swans, greater white-fronted geese and bean geese have been gathering there in the winter thaw (Photo 3). Japanese cranes (red-crowned cranes) now mostly seen in the Kushiro Shitsugen wetlands are spreading to other wetlands and abandoned farmlands in Hokkaido as well, and these areas are expected to function as important breeding grounds. It will not be a pipe dream to see Japanese cranes “dancing” in the snowfields close to Chitose Airport. Should we chase for material richness as we have done so far? Or, should we chase for spiritual richness brought by natural capital (values inherent to the natural environment such as air, water, soil and living things)? Japan is standing at the crossroads.

Related Websites

Forest Ecosystem Management Laboratory, Hokkaido University, Japan

http://forman-eco.blogspot.jp/

http://www.agr.hokudai.ac.jp/formac/forman/

Profile of Futoshi Nakamura

Dr. Futoshi Nakamura was born in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture in 1958. He entered Hokkaido University to satisfy a longing for Hokkaido since junior high school. At first, he was going to specialize in engineering, but he changed his direction to major in forestry under the influence of his friends of the brown bear collegium and the words by Prof. William Smith Clark of Sapporo Agricultural College (now known as Hokkaido University), “Boys, be ambitious.” He earned his Ph.D. in Agriculture from Hokkaido University in 1987.

From 1990 to 1992, Dr. Nakamura studied ecosystem management at Oregon State University. His major interest is the interactions in ecosystems such as connections of forests and rivers. He has studied this field from a perspective of watersheds including land use and his activities extend over a wide range of fields. He has played an active role not only in the field of application including forestry and applied ecological engineering, but also in the field of basic science including geomorphology and ecology. He serves as a member of editorial boards of international journals including Geomorphology, Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, Landscape and Ecological Engineering, and Riparian Ecology and Conservation.

Dr. Nakamura was awarded the Japanese Forest Society Award in 2005, Biwako Prize for Ecology in 2009, Oze Prize in 2011 and The MIDORI Academic Prize in 2012. He holds several positions such as vice president of the Japanese Forest Society; vice president of the Ecology and Civil Engineering Society; expert of the Central Environmental Council; member of the Nature Restoration Promotion Conference; president of the Nature Restoration Committee for Kushiro Shitsugen Wetland. His major publications include: “Mizubeikikanri (in Japanese, Management of Riparian Zone)” (Kokon Shoin); “Shinrin no Kagaku (in Japanese, Forest Science)” (Asakura Publishing Co., Ltd.); “Kawa no Kankyomokuhyo wo Kangaeru (in Japanese, Thinking about the Environmental Targets of Rivers)” (Gihodo Shuppan); “Kawa no Dakohukugen (in Japanese, Restoration of S-shaped Rivers)” (Gihodo Shuppan)”; “Kasenseitaigaku (in Japanese, River Ecosystem)” (Kodansha Scientific).