Why does biodiversity matter?

- Christopher Lloyd

- Journalist, Author, Publisher and Lecturer

ACTUALLY the question is a lot harder to answer than it seems. It is true that many people have an instinctive appreciation for the natural world - its beauty, its variety and our dependence on nature for survival in the form of food and resources. But now a majority of the world’s 7.1 billion humans are living in towns and cities, our instinctive attachment to nature is in danger of being lost.

Protestations by environmentalists trying to save from extinction species that have no possible use to humanity come across as increasingly weak and detached from the mainstream reality of urban living. It really isn’t enough nowadays simply to say we must preserve biodiversity – much more important is to explain why? Without a fundamental rationale that makes biodiversity a core concern for every human on the planet, the battle to create a sustainable future will continue be lost.

So let me post the question again – why does biodiversity matter? Why can’t humans simply focus on the species that best provide them with want they want and need most: food, shelter, comfort, beauty and leisure? Afterall, these are the selection criteria that matter most today if you are non-human species.

Rice is very successful and so are chickens (apparently 24 billion are alive at any one time on the earth, making chicken genes considerably more successful than human genes). Fast-growing eucalyptus trees provide us with cheap paper and fence posts thrive in vast plantations. Dogs and cats give lonely people and young children a love of life. Roses and lotus flowers appeal to our sense of visual beauty and symmetry. Coffee and tea do things to our heads that make use feel stimulated or relaxed.

So why don’t we simply focus on preserving those few species that make life for humans on the planet Earth pleasant? So what if amphibians are dying out. Except for in France, where frogs legs are a delicacy, they would hardly be missed. So what if the African Rhino or the Indian tiger is on the verge of extinction? Who needs creatures from a bygone age in a world with billions of humans living in vast towns and cities? Apart from being curiosities at the zoo, these creatures are simply not relevant in today’s world and so nature is doing what it does best to irrelevant creatures – it makes them extinct. You can’t really blame humans for this purge of wildlife – afterall, we are simply part of the natural system. And a very successful part at that.

These are the kinds of underlying objections that face the biggest challenge of all to environmentalists who, because they care about the natural world, are desperate to win the argument for preserving the Earth’s biodiversity. Unfortunately, it is largely their failure to communicate and win this argument that accounts for why the battle to preserve the world’s species is being lost.

I have spent the last 6 years trying to find ways of making people enjoy and appreciate the most magical, non-fiction narrative of all – the story of planet, life and people as it has evolved over the last four billion years. This big history perspective is not commonly taught at schools because modern educators are obsessed with an outdated Victorian idea of serving up knowledge to young people as a series of disconnected curriculum fragments. As a result the perspective of seeing humans as an inextricably interconnected species dependant on all others for its survival and welfare is lost.

Young people, born to be curious about nature, are unable to follow their natural learning instinct - curiosity - to make sense of a world of knowledge smashed into pieces like a pane of shattered glass. Eventually they get bored and learn simply what they are told they need to know.

A series of disconnected, disjointed chunks of information cannot possibly paint a big picture: past, present or future. Sadly, this educational disease is as prevalent in Asia as much as it is in Europe and America, since a Western habit of reducing education into a fragmented, silo-driven approach was, unhappily, exported all over the world as its influence predominated throughout the 20th century.

Therefore, in order a win the argument about why biodiversity maters, a big picture approach to learning has to be established alongside, and in addition to, focused, specialist study. We must find ways of learning that help young people ‘zoom out’ to see the big picture consequences of the modern proliferation of human culture into every corner of the biosphere.

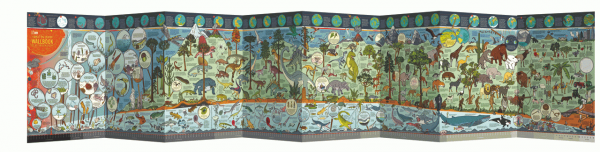

I have tried to do this by making a timeline of 1,000 species beginning with the emergence of the first bacteria, nearly 4 billion years ago, and culminating with a world filled with 7.1 billion humans today. I have also written a book called What on Earth Evolved? 100 Species that Changed the World which tells the story of the most successful non-human species and how inextricably our past, present and future is interlinked with other living things. And I follow up all possible opportunities to visit schools, conferences, museums and literary festivals with a big picture approach to learning, connecting the dots of past.

The most important message that precipitates from these big narratives (visual, textural or dramatic) is that biodiversity matters because it is life’s one and only insurance policy against mass extinction.

Luckily, people living in towns and cities understand what an insurance policy is because they spend billions of pounds alleviating an increasing modern sense of insecurity through the purchase of everything from protection against theft or accidental loss to personal liability in the event of legal action. Today most people insure themselves against everything, everywhere, all the time – from homes and cars, to holidays and lives. The more urban we become, the more insurance we seek. The amount of money spent globally on insurance is beyond all reasonable measure.

Biodiversity matters because it provides nature’s insurance policy against extinction. Without variety in the ecosystem, nature cannot bounce back or adapt when the environment changes. Biodiversity is the fundamental self-correcting pivot around which nature has been able to sustain itself despite an endlessly changing environment over nearly 4 billion years.

Without biodiversity there would have been no endosymbiosis - the remarkable event that led to the emergence of all higher forms of life from plants and fungi to animals and humans. As rising levels of oxygen threatened many bacteria with extinction 2 billion years ago, they adapted by creating complex cells to avoid toxic shock.

Without biodiversity creatures in the Cambrian era seas would never have adapted to living in a world where some animals (trilobites) developed eye-sight. The advent of the era of active predation – triggered by clear underwater vision - meant shells, bones, teeth, camouflage and burying underground quickly became keys to survival. Without the diversity of life, creatures with the best attributes for survival against creatures with eyesight could never have emerged as life newest success stories.

Without biodiversity reptiles would never have ruled life on land. In a world dominated by a single giant supercontinent Pangaea, giving birth inland with waterproof hard-shelled eggs became a key survival advantage.

Without biodiversity mammals would never have thrived 65 million years ago when a meteorite strike killed off the terrestrial dinosaurs. The mammals’ ability to hunt in the dark and their acute sense of smell gave them a critical advantage during the trauma of a year long night when the sun was blocked out by meteoric dust.

Without biodiversity human ancestors would never have adapted to walk on two feet as a way of seeing into the distance. It happened when trees were replaced by grasslands when rainfall levels in Africa fell blow those needed to sustain forests as a result of the ice age. Walking on two feet led to tool making using our freely available hands and the rest is, literally, history.

Without biodiversity viruses would have annihilated human populations aeons ago. If we all shared the same genetic code all it would take is one successful virus attack to wipe us all off the face of the earth.

Biodiversity is the key insurance policy that allows living systems to adapt. We destroy it not only at our own peril, but also we risk destroying the system used by life to recover from major extinction traumas which will inevitable strike sometime in the future (man made climate change, perhaps?).

Biology cannot persist in a world dominated by a limited range of genetic entities that only suit just one prolific species homo ‘sapiens.’ Monocultures are unsustainable because they are not configured to be able to adapt to change. They are not natural self-correcting systems.

Ultimately it is biodiversity that underpins all the money invested in financial insurance schemes everywhere throughout the urban world, because with out it there would be no world to insure.

Fragmented curriculums, specialist-only knowledge and silo-driven learning are the real enemies of this critical message. Without changing them, without constructing an easy-to-comprehend giant narrative that connects the dots of the world around us, the question: “Why biodiversity matters?” can never effectively be answered.

Profile of Christopher Lloyd

Mr. Christopher Lloyd has had a broad and comprehensive career as a journalist, author, publisher and lecturer.

Mr. Lloyd graduated from Peterhouse, Cambridge in 1991 with a double first-class degree in History.

After graduated from the university, he served as journalist for The Sunday Times newspaper. In 1997, he launched the first Internet edition of The Sunday Times and became its Internet editor. In 1997 Mr. Lloyd co-founded LineOne, a joint venture Internet Service business and became its editorial director. In 1999 he proposed the development of a network of internet related businesses at News International, and created new revenues for the newspaper business.

In January 2001, Mr. Lloyd was recruited to become chief executive of Immersive Education, an education software publishing company. He grew the company from its R&D phase with zero revenue to sales of in excess of ₤3 million.

In 2006 he left Immersive Education to spend time travelling around Europe with his wife and two children, both of whom are home-educated. The time spent on the road travelling around Europe inspired him to come up with the concept of What on Earth Happened? At present, “What on Earth Happened? The Complete Story of Planet, Life and People from the Big Bang to the Present Day” and “What on Earth Evolved? 100 Species that Changed the World” are in published.

In February 2010 he set up a new publishing venture to pioneer new ways of telling global narratives using illustrated publications that can be read like conventional books or unfolded and stuck on a wall (read about the ethos and aims of What on Earth Publishing Ltd). The company’s first book, The What on Earth? Wallbook has sold more than 50,000 copies in the UK and has been translated into vairious languages. There is a series of FIVE Wallbook in development, four of which have been published.

Mr. Lloyd now divides his time between writing, publishing and giving lectures throughout the UK and internationally to schools, universities, museums and literary festivals.

Major Books:

What on Earth Evolved? 100 Species that Changed the World (2009)

The What on Earth? Wallbook (2010)

What on Earth? Wallbook of Natural History (2011)

What on Earth? Wallbook of Sport (2012)

What on Earth? Wallbook of Science & Engineering (2013)

What on Earth? Wallbook of Shakespeare (to be published in 2014)