An Encouragement of Jimoto-gaku – Local Area Studies

- Jun-ichi Takeda

- Secretary General of Support Center for Rural Communities, Tokyo University of Agriculture

Judge of the Japan Awards for Biodiversity 2015 Judging Committee

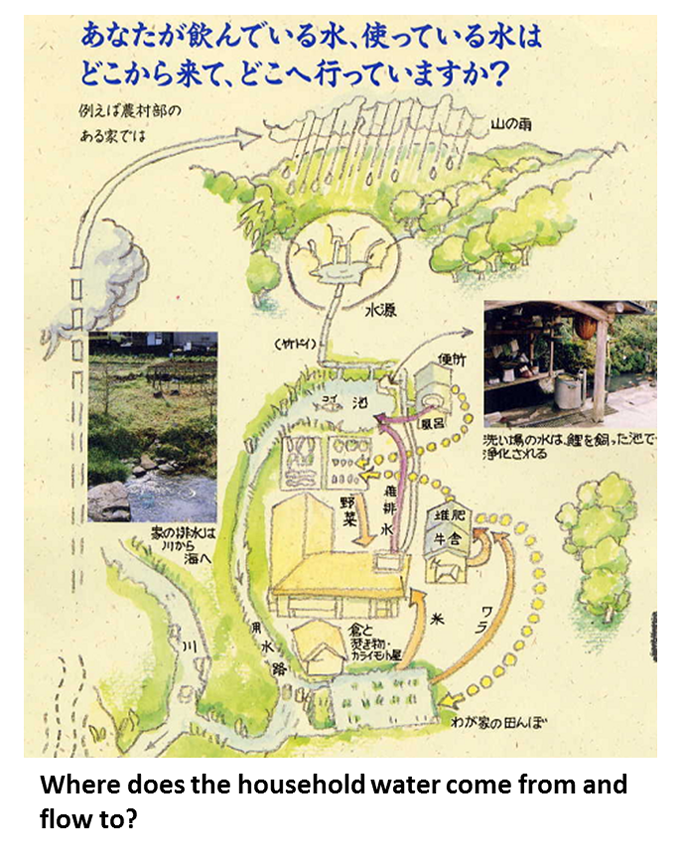

Where does the household water come from, and where does it flow to? Have you ever been to your water’s source? What state is the surrounding forest in?

The answers to these questions might come easy to senior citizens who live on a satoyama or community-based forest, but may be difficult for those who do not live so “close to the land.” I imagine few inhabitants of urban areas know where their water comes from, the pipe route from source to faucet, and the route their drains take. But pursuing jimoto-gaku techniques throughout Japan to map villages’ water routes and identify local resources have enabled us to learn about how many villages were established.

The answers to these questions might come easy to senior citizens who live on a satoyama or community-based forest, but may be difficult for those who do not live so “close to the land.” I imagine few inhabitants of urban areas know where their water comes from, the pipe route from source to faucet, and the route their drains take. But pursuing jimoto-gaku techniques throughout Japan to map villages’ water routes and identify local resources have enabled us to learn about how many villages were established.

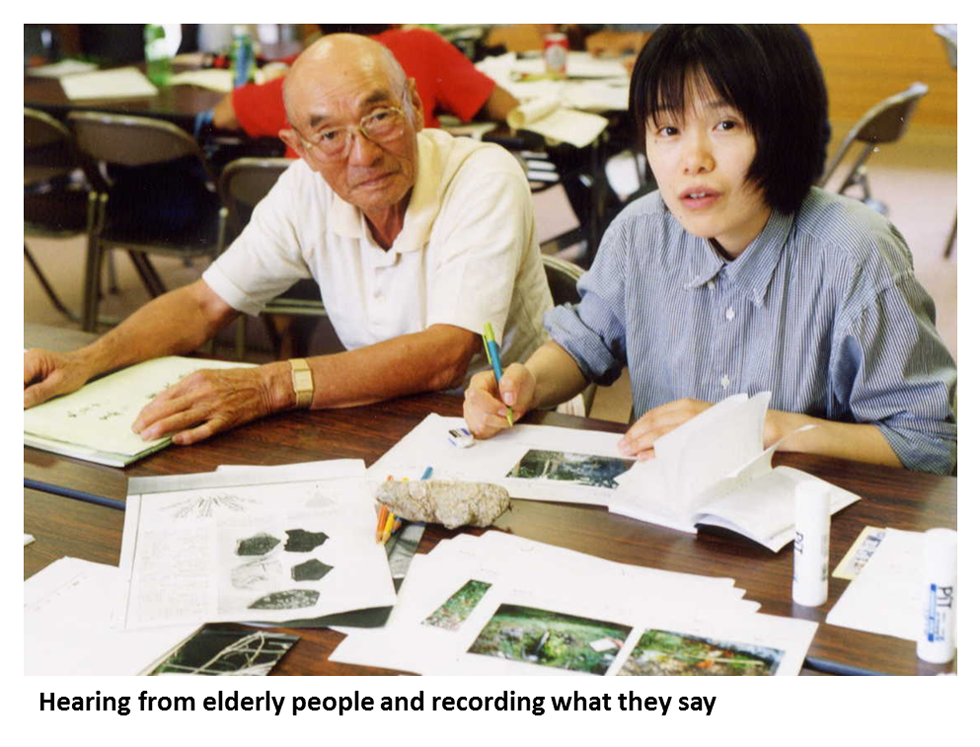

Examining the livelihoods of senior citizens in remote mountain villages close to okuyama, deep mountain areas, provides a view of water-use wisdom and the unique local mountain village culture – wisdom and culture that has continued across the ages from times of hunting and gathering when chestnuts and other mountain produce were a major food source, through to the present age of forest management, when charcoal is fuel, and woods are raw materials for production. By performing a jimoto-gaku study with senior citizens, we can see springs that produce roughly the same amount year-round and crystal-clear mountain streams, and by tracing the route that this water takes to the village, understand that this water is the starting point from which the village formed.

Identifying water sources provides an opportunity for making records, because it involves asking about information such as the state of forest management around the water source, watersheds between the source and the village by means of the water’s route, agricultural irrigation water routes, the kinds of organisms found near water routes, and the history of water disputes. Satoyama villages near plains were formed when people began to create paddies and farm the land in proximity to springs and wells in local valleys. So important is the water source that, in some regions, the sites are consecrated, shrines are built, and sacred forests are established. Elsewhere, forests that have no impact on water sources are administered as fuel wood and thatch-reed fields. This encourages coppicing, which in turn provides water for agricultural use, fertilizers (e.g. composted fallen leaves and wood ash), tools, and construction material.

Satoyama villages near plains were formed when people began to create paddies and farm the land in proximity to springs and wells in local valleys. So important is the water source that, in some regions, the sites are consecrated, shrines are built, and sacred forests are established. Elsewhere, forests that have no impact on water sources are administered as fuel wood and thatch-reed fields. This encourages coppicing, which in turn provides water for agricultural use, fertilizers (e.g. composted fallen leaves and wood ash), tools, and construction material.

In regions bordered by water such as Omihachiman on the shores of Lake Biwa, people still use wells as part of their daily lives. The houses of this town, which developed with samurai estates and thrived as a commercial area, were built along veins of good underground water.

In this way, the size of a village on a satoyama and the number of households, people living there, drinking water, rice paddies, farming, the number of livestock and the like are determined naturally in accordance with the quality and quantity of water. Indeed, using the jimoto-gaku technique of mapping of water routes changes the way residents view their own villages. Those who do so soon understand the depth of wisdom that went into their village’s water use – which has continued from one’s ancestors, and recognize the need to influence nature and manage it on an everyday basis.

I grew up in a village in a small valley in Machida, Tokyo. There, too, I notice that the remnants of dwellings in caves and pits are to be found near the village’s water source, and I was surprised to find that over thousands of years that the number of dwellings stays at roughly ten – meaning that the village has maintained a dynamic equilibrium over all those decades.

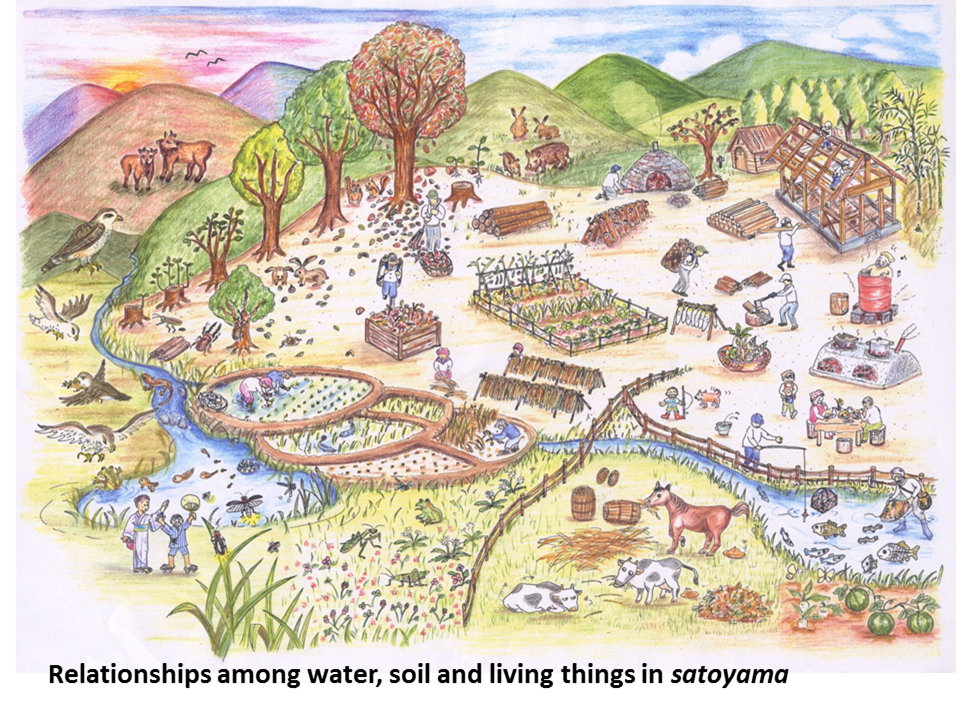

To my mind, a village nestled in a valley and surrounded by a satoyama is the epitome of sustainable society and a microcosm of society in harmony with nature.

We seek to enrich livelihoods in the village by providing diverse habitats for all living things. We do this by arranging different types of aquatic environments routes for drinking water, ponds, streams, and routes for water for rice paddies. A water map for people provides a diverse habitat for living things.

Near your home, are there any edible plants, medicinal plants, or other hunt-and-gather food sources?

People able to answer these questions are those who enjoy making use of the blessings of a satoyama and its ecosystem. The people who live on a satoyama, who are a minority these days, carry out their lives coexisting with nature. If we ask senior citizens who live on a satoyama, they would be instantly able to identify several dozens of plants. In particular, we learn that many are gathered on paths near mountain streams. If we are able to collect edible wild plants and medicinal herbs in our inspection of a water source, we would be able to collect the blessings of the satoyama through basic work to sustain one’s livelihood.

People able to answer these questions are those who enjoy making use of the blessings of a satoyama and its ecosystem. The people who live on a satoyama, who are a minority these days, carry out their lives coexisting with nature. If we ask senior citizens who live on a satoyama, they would be instantly able to identify several dozens of plants. In particular, we learn that many are gathered on paths near mountain streams. If we are able to collect edible wild plants and medicinal herbs in our inspection of a water source, we would be able to collect the blessings of the satoyama through basic work to sustain one’s livelihood.

What we learn from a jimoto-gaku study is that life on a satoyama is fruitful as it received nature’s blessings. This is a self-sufficient livelihood that I much admire when I compare it to my own life as an urban consumer. From home gardens to rice fields and thatch-reed fields, satoyama community-based forests, and deeper mountains, a village encompasses a whole satoyama “garden.” The more the villagers, the better the management of this garden; but fewer managers means management suffers – the satoyama first, then the fields and home gardens. The beautiful face of the village – the satoyama – is lost. Views of the satoyama doesn’t just mean the landscape, but also houses and homes, kimono kept in storehouses, lacquerware, tools, saplings, tools by the side of the well, stables and cowsheds.

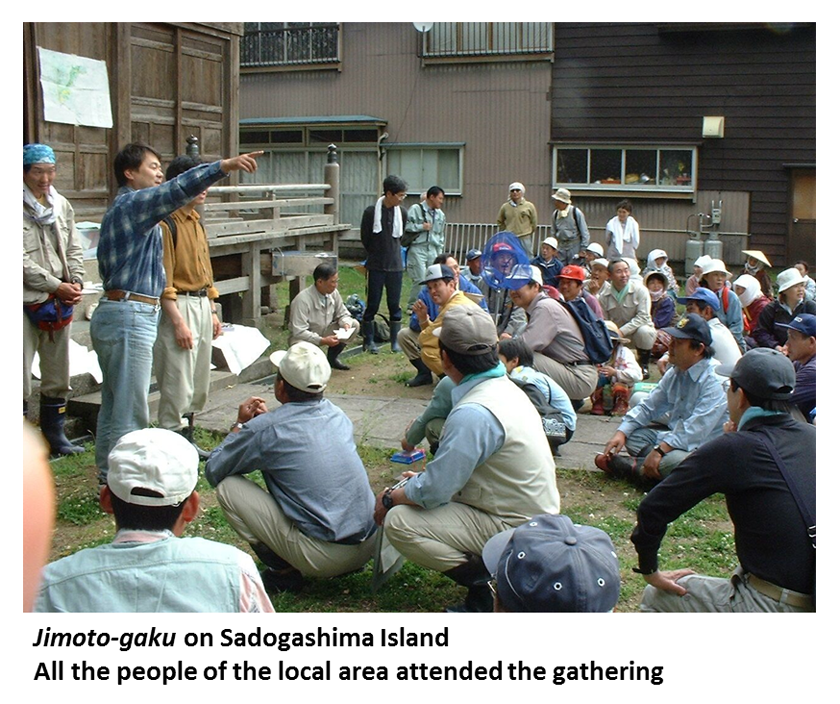

jimoto-gaku is the work by a village to map their long-standing way-of-life and culture, and inventory local resources; indeed, it reflects life in the village. How would we write the future of the village? For example, preparation for the return to the wild of the Japanese crested ibis began on Sado Island in 2000. The Ministry of the Environment put forth a plan to release the birds when they reach 100 in number (Crested Ibis Reintroduction and Environmental Regeneration Vision). This vision was communicated to other ministries and local government bodies, and a council was set up to start discussion.

On Sado Island, we carried out jimoto-gaku studies through the villages for the purposes of this plan. We climbed mountains to find water sources, and created maps of water routes. We discovered that spring water, a cool 11 degrees all year round, runs through the paddies directly below water sources. As the water is too cold for rice production, it has to be warmed. We made pools to collect and warm the water in paddy fields, and thereby encouraged rice plants to grow. Many creatures were attracted to these pools, including yokoebi crustaceans, dragonfly larvae, Japanese water beetles, water scorpions, salamanders and loaches. It was an oasis for them, with a steady temperature year-round. In order for the Japanese crested ibis to visit the area in the future, we started created places for the bird to feed in the villages – going from water sources down to the ocean, following water routes. The rice is directly sold and delivered to people who support the crested ibis, and also sold through shops who support the initiative.

The discovery of Abe salamander in Echizen (previously known as Takefu), Fukui, led to a request from the prefectural government to help protect the local Abe salamander population in 2002. Based on previous studies, we conducted an all-hands jimoto-gaku study in order to create a habitat environment. Village homes are built to face the satoyama. The village is one with wells in caves. The water source for each household has evolved from cave well to well water to public waterworks, but the wells are still active. We improved the surrounding aquatic environment of these cave wells, and created a habitat for many creatures, starting with diatoms, yokoebi crustaceans, and the Abe salamander. The brooks and marshland, created as a buffer between spring water and the paddies, became the ideal habitat for Abe salamander larvae. This initiative was widened to incorporate an old, disused part of the village, as well as the adjoining village, and we worked to conserve the ecosystem. The region has earned broad praise for creating a home for the oriental stork.

What is jimoto-gaku? How do you practice it?

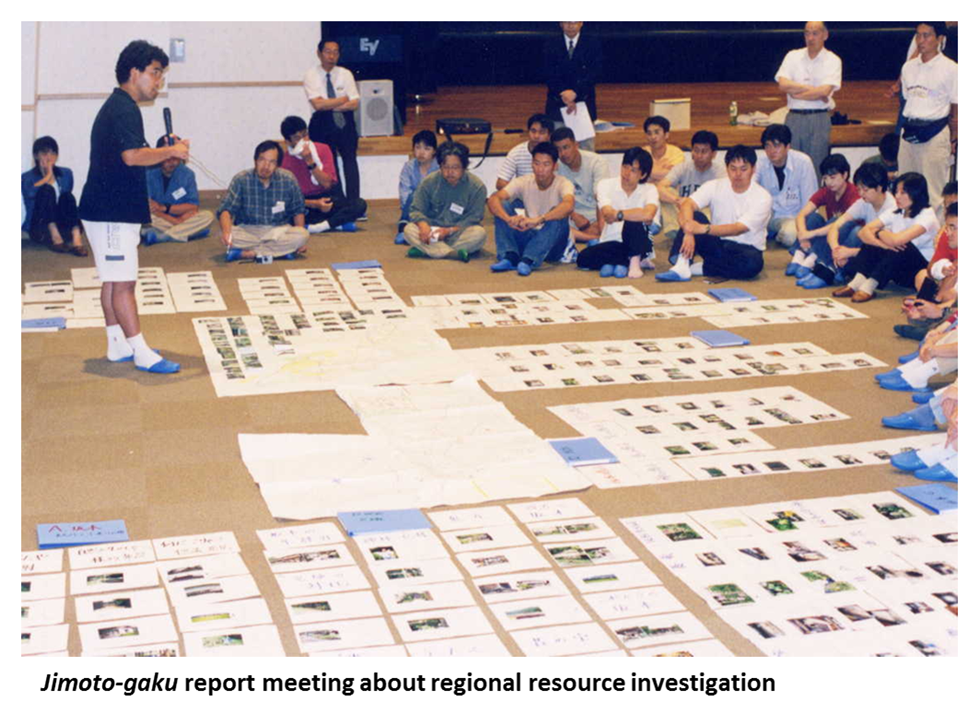

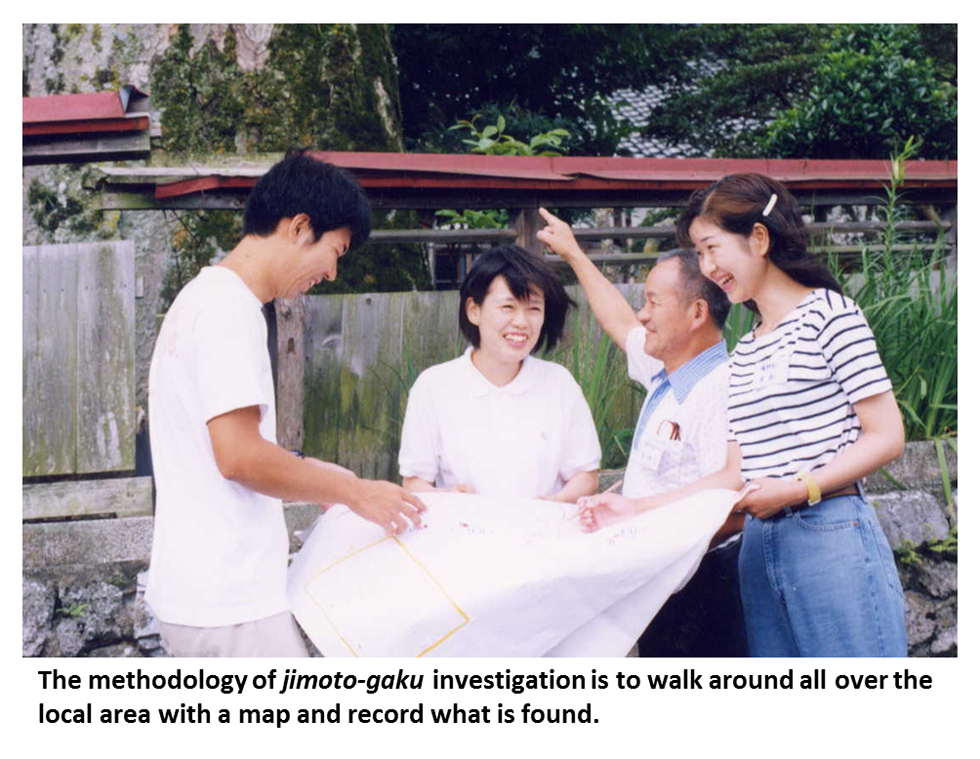

jimoto-gaku is learning from local areas. The jimoto-gaku I talk about is where people walk and investigate their local region – with help from outsiders – talk about their discoveries, and develop their future livelihood in that region based on this study. The process of actually investigating and rediscovering the local area stimulates communication within the region, and inhabitants come to see a future for the local area they live in, as well as concepts and things that need to be passed on to their children or grandchildren. jimoto-gaku is not an existing area of study, but is study put into practice as the people who investigate and participate become more knowledgeable.

jimoto-gaku is learning from local areas. The jimoto-gaku I talk about is where people walk and investigate their local region – with help from outsiders – talk about their discoveries, and develop their future livelihood in that region based on this study. The process of actually investigating and rediscovering the local area stimulates communication within the region, and inhabitants come to see a future for the local area they live in, as well as concepts and things that need to be passed on to their children or grandchildren. jimoto-gaku is not an existing area of study, but is study put into practice as the people who investigate and participate become more knowledgeable.

Who participates?

jimoto-gaku is performed by a mix of local residents and outsiders.

jimoto-gaku is performed by a mix of local residents and outsiders.

The jimoto-gaku teachers are people with close ties to the local area – grandfathers, grandmothers, people involved in agriculture, forestry or fisheries, craftspeople such as carpenters, and children who play in the hills and fields. The students are the parents and children, whose links to the area have faded in the modern era. jimoto-gaku also involves things that local people see as ordinary, but are a surprise to visitors from outside. That’s because it’s different to the ordinary for the visitor. Surprises and discoveries are made from differences. Each of these is important to the region’s character.

Will jimoto-gaku enable us to develop our region?

In a word, no. jimoto-gaku is a technique by which the way of living, wisdom and technology passed on from a village’s past is investigated by a local village inhabitant walking around and becoming knowledgeable – where everyone comes to know how the structure of the village, the map of water routes, play areas, habitat areas for living creatures, and learning expert techniques for hunting, forestry, farming, processing, and masonry. Carrying out jimoto-gaku and having village inhabitants become more knowledgeable about the local area means the basics of regional development have been formed. You can draw a future shape based on information shared by everyone. Taking this vision of the future, you can start regional development based on changes to each person’s values and mutual understanding obtained through jimoto-gaku, and advance consensus building. Together, appropriately facilitated jimoto-gaku and regional development can help revitalize your satoyama. To me, jimoto-gaku is a philosophy awakening us to look toward the realization of society living in harmony with nature.

More about jimoto-gaku

Ecotourism and jimoto-gaku (local area studies)

Profile of Jun-ichi Takeda

Mr. Takeda was born in Tokyo, Japan and graduated from the Faculty of Law, Chuo University. Following service at a financial institution, a UK think-tank for technology development and a NPO, now Mr. Takeda holds several positions including Secretary General of the Support Center for Rural Communities, Tokyo University of Agriculture; Head of Secretariat, Mori-sato-kawa-umi Nariwai Institute and Satochi Network; Director of Environmental Partnership Council; Director of Network for Coexistence with Nature; and Lecturer of Chuo University. He also serves as an evangelist for regional activation.

Mr. Takeda has promoted jimoto-gaku (local area studies) and made contributions to conservation and restoration activities of satochi satoyama. He has established spontaneous human networks among people engaged in circulation in local areas, and promoted co-existence among humans, the co-existence of humans and nature, and resident-driven and citizen participatory regional development. Also, he has been engaged in designing basic policies for local cooperative conservation activities and developing various proposals and guidelines adopted by related ministries and agencies. In addition, he has supported diverse activities such as investigations, research, technology development, meetings, lectures, and information transmission to media.

Mr. Takeda’s representative books (joint authorship) include: “Mori-sato-kawa-umi no Shizen-saisei (in Japanese, Nature Restoration, Forests, Rural Areas, Rivers and Oceans)(Chuohoki Publishing Co., Ltd.), ” “Minamata no Arukikata (in Japanese, How to Walk Around Minamata)(Godo Shuppan Co., Ltd.),” “Jissen Community Business (in Japanese, Practical Community Business)(Chuo University Press),” “2100 nen Mirai no Machi e (in Japanese, For Future Towns in 2100)(Shogakukan Inc.),” and “Nihon Housei no Kaikaku: Rippo to Jitsumu no Saizensen (in Japanese, Legal System Reform in Japan, The Forefront of Practical Legislation)(Chuo University Press).”

Mr. Takeda’s major projects include:

Review of satochi satoyama conservation measures and development of modelling areas (Ministry of the Environment)

Development of satochi environment where humans live in harmony with nature (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Ministry of the Environment)

Livelihoods making best use of satoyama forests (Forestry Agency)

Guidelines for activating local areas using renewable energies (Forestry Agency)

Promotion of biodiversity in social capital (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism)

Regional society development based on co-existence and circulation, Toward the return of toki into the wild (Ministry of the Environment, Local Government of Niigata Prefecture)

Conservation of Abe's salamander and regional development (Ministry of the Environment, Local Government of Fukui Prefecture)

Secretariat for the best 30 satochi satoyama conservation and utilization contest (The Yomiuri Shimbun, Ministry of the Environment)

AEON satochi satoyama conservation activities (AEON Environmental Foundation)

Technology development and experimental study for global warming (bamboo tube fuel) (Ministry of the Environment)