Pachamama, Mother Earth

- Bibiana Vilá

- Director, Vicuñas, Camelids and Environment (VICAM)

Principal Researcher, National Research Council (CONICET) Argentina

The MIDORI Prize for Biodiversity 2014 Prize Winner

The first day of August is Pachamama day, and along the month, people in the Andes ask Mother Earth for her blessings. August, the end of winter, is the month of greatest hardship in the Altiplano, that is, when the living conditions are at their most difficult with windy and arid conditions as well as freezing temperatures. This is the time "to feed the Earth-Pachamama” and the beginning of the new agricultural and breeding year.

The first day of August is Pachamama day, and along the month, people in the Andes ask Mother Earth for her blessings. August, the end of winter, is the month of greatest hardship in the Altiplano, that is, when the living conditions are at their most difficult with windy and arid conditions as well as freezing temperatures. This is the time "to feed the Earth-Pachamama” and the beginning of the new agricultural and breeding year.

The Altiplano is a central Andean highland semi-desert plateau located at more than 3,500 meters above sea level. It is characterized by dry, cold weather and vegetation adapted to arid conditions. The original fauna of the Altiplano includes the wild South American Camelids: Vicuñas (Vicugna vicugna), and guanacos (Lama guanicoe) and their domesticated derivates, the alpaca (Lama pacos) and llama (Lama glama). The Altiplano is inhabited by aboriginal Quechua and Aymara speaking communities that are the descendants of the people who lived in the Inca Empire. Many of these rural communities are traditional herders of domestic camelids – llamas and alpacas – as well as sheep and goats. In the lower valleys and in small areas of the Altiplano, an agriculture of potatoes, quinoa and maize has developed.

“The Earth does not belong to us, but we belong to it, because we are her sons and daughters. Who owns the land? Pachamama is our mother and in this home we live as humans, animals and plants.”

These words belong to René Machaca, a local primary teacher living in the Argentine Andes. I chose them as they reflect on the multidimensionality and the difficulty of cataloguing the concept of the Pachamama. Pachamama is a deity – she is the goddess-mother, giver of life – but she is also the Earth, the actual ground where we plant the seeds and over which we walk. As a deity she has immense power, but she must also be nurtured and cared for, in her physical, real and material sense. Another perspective on this theme is that the life that the Pachamama gives has different representations, with humans just one of these possible expressions, and as such not a different one from animals and plants. René Machaca, a teacher, introduces us to the complexity of the Pachamama concept through his everyday words – Pachamama as the deified earth and as the maternal supernatural entity.

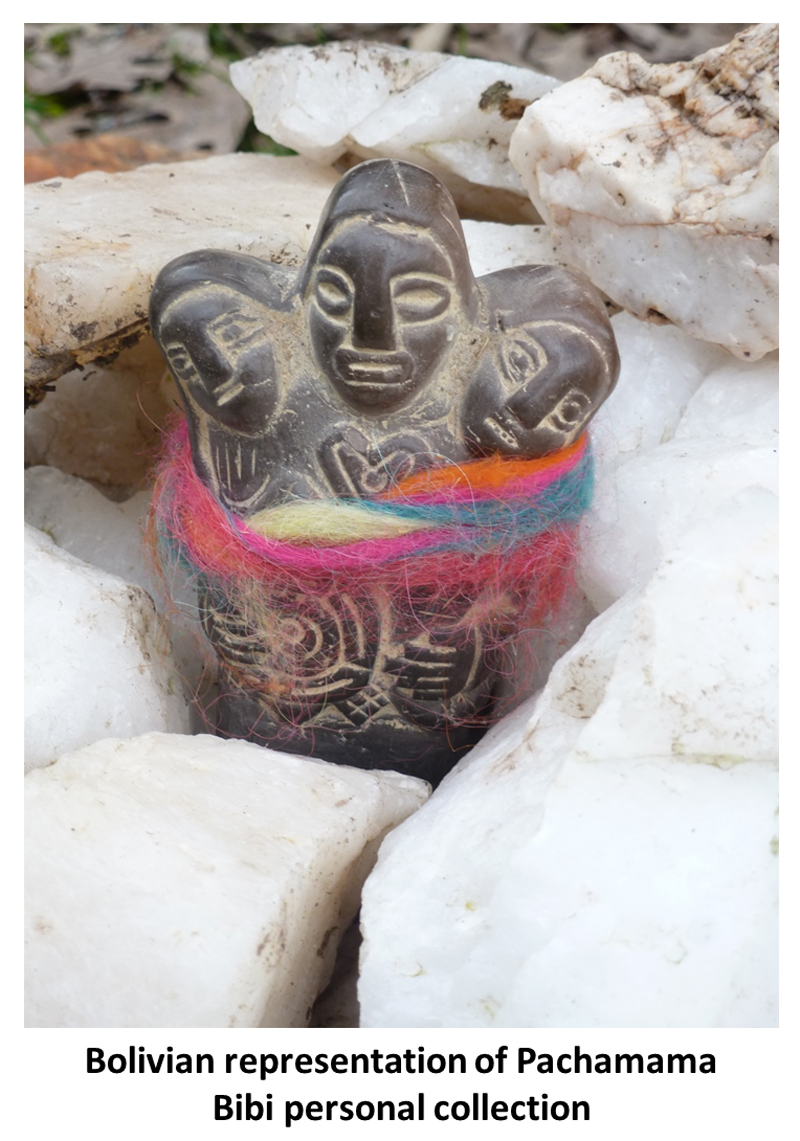

Before the Spanish arrived to the Americas, Prehispanic civilizations venerated the Earth in multiple ways. This can be seen clearly in archeological remains. The Inca Empire venerated the Sun (Inti), and the Earth or Pachamama. The word Pachamama is already documented by the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th Century among both Quechua and Aymara indigenous groups. Pacha means Earth – world, landscape, land, soil and time – while mama means mother – soul and essence. Although the Spanish imposed Catholicism in the region, violently suppressing the supposed local heresy as well as destroying any indigenous religious symbols, the cult to the Pachamama survived through syncretism with the Christian Virgin Mary. At present, the Pachamama is venerated principally because of her fertility, but beyond that she is also admired as a female deity in her own right with particular virtues, appearance, presence, character and powers.

Pachamama is represented as a little old woman who lives underground or in the mountains. She wears traditional Andean clothes made of the finest vicuña (Vicugna vicugna) fiber, likewise she is always spinning, vicuña fiber with her spindle. In recent times, representations of the Pachamama as a young and powerful woman at the prime of her life have become common. According to indigenous belief, she is our mother, yet the Pachamama is not only the mother of humanity but also of the mountains, the Twins – Sun and Moon –, domestic animals, and crops.

Given the sacredness of the Earth, whenever a natural resource is taken, permission of the Pacha has to be invoked, and an offering made. For instance, potters do this whenever they remove clay from its source. In preparing the land for seed planting, small lady amulets are buried in the earth as Pachamama offerings. The tutelary function of the Pachamama includes many traditional activities such as weaving, spinning and pottery making.

Given the sacredness of the Earth, whenever a natural resource is taken, permission of the Pacha has to be invoked, and an offering made. For instance, potters do this whenever they remove clay from its source. In preparing the land for seed planting, small lady amulets are buried in the earth as Pachamama offerings. The tutelary function of the Pachamama includes many traditional activities such as weaving, spinning and pottery making.

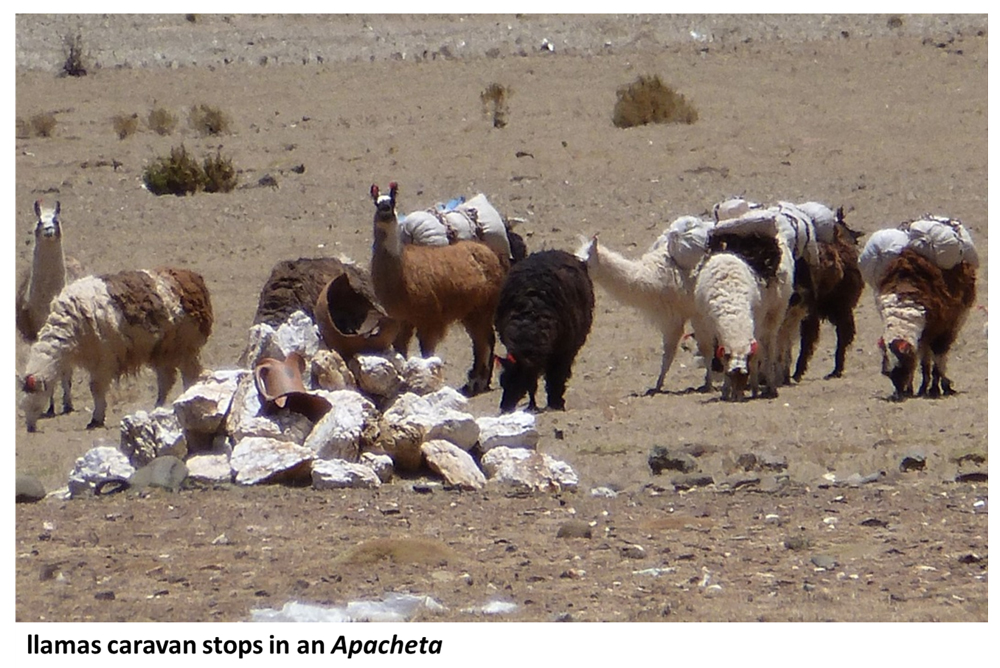

The Pachamama places of worship comprise unique natural rock formations, mountains, special rocks or stones grouped together by the people to form "cairns" or apachetas. High altitude snowy mountains, the highest peaks, and volcanoes are sacred because in traditional Andean religion, humans originally emerged from the interior of the Pachama place where the Pachamama also resided, thereby highlighting the duality of place and deity. These sanctuaries are usually sited on high mountains, so that the journey itself involves ascending into the sacredness of nature. Places inside mountains, such as caves, are objects of veneration as well as springs and rivers that originate in the mountains.

The cairns are located alongside roads, where walkers can call on the Pachamama, place a further stone on the pile thus assuaging their weariness. People can also go to the apacheta to ask for conflict resolution, health, or the removal of curses. Particular cairns, known as pachamamas, are situated near corrals with white stones representing llamas, so that a newly added stone to the pile is in fact a magical-propitiatory appeal to increase the flock.

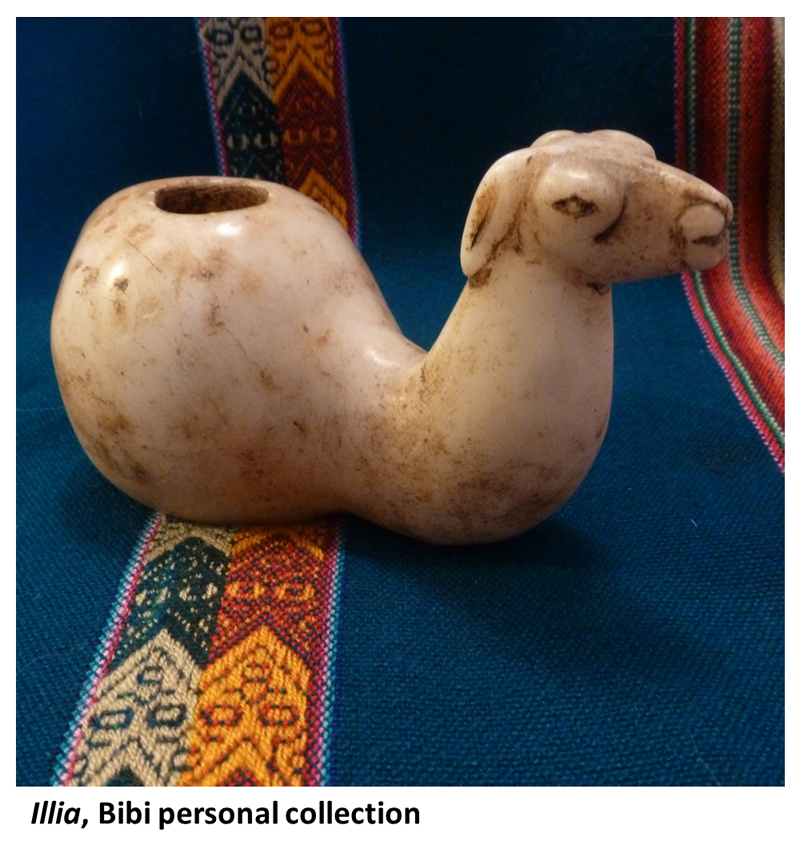

The offerings to the Pachamama include amulets and talismans, known as illa, some of them are natural – rocks, minerals, stomach bezoars – while others are manufactured. For most ceremonies, especially those held on the 1st of August – the day of the Pachamama – the offerings are placed on a cloth, either on the floor or on a table. Food and beverages are buried in a small pit near a sacred rock together with a talisman carved in stone or molded in metal representing a zoomorphically rendered llama.

The offerings to the Pachamama include amulets and talismans, known as illa, some of them are natural – rocks, minerals, stomach bezoars – while others are manufactured. For most ceremonies, especially those held on the 1st of August – the day of the Pachamama – the offerings are placed on a cloth, either on the floor or on a table. Food and beverages are buried in a small pit near a sacred rock together with a talisman carved in stone or molded in metal representing a zoomorphically rendered llama.

The coca leaf (Erythroxylon coca)is a sacred plant, and represents one of the most common offerings used in Andean religion. Coa, (Lepidophyllum sp) is a resinous aromatic plant used to create smoke in ceremonies. The “wira” or pericardial fat of the llamas is also used for smoke and is considered together with the desiccated fetuses of llamas – sullu – a powerful magic substance. Other offerings include red-dyed llama wool, maize, food, tobacco, flowers, and alcoholic drinks such as chicha – made from fermented maize, beer and wine. Most offerings are placed into a ceremonial pit dug into the earth. Some offerings relating to livestock are buried in corrals and in their grazing and watering areas. These offerings are often placed while intoning Pachamama, Holy Earth, we beg you that your fruitful and generous uterus give us pastures for our llamas. On special communal occasions a llama is sacrificed to the Pachama with the blood of the llama being offered to the Earth, while the animal is consumed as part of a collective ceremonial meal. Veneration of the Pachamama carries over to people´s houses, where sacred stones – usually white quartz rounded by red wool rings – are placed, referencing the protection of the Pachamama.

The coca leaf (Erythroxylon coca)is a sacred plant, and represents one of the most common offerings used in Andean religion. Coa, (Lepidophyllum sp) is a resinous aromatic plant used to create smoke in ceremonies. The “wira” or pericardial fat of the llamas is also used for smoke and is considered together with the desiccated fetuses of llamas – sullu – a powerful magic substance. Other offerings include red-dyed llama wool, maize, food, tobacco, flowers, and alcoholic drinks such as chicha – made from fermented maize, beer and wine. Most offerings are placed into a ceremonial pit dug into the earth. Some offerings relating to livestock are buried in corrals and in their grazing and watering areas. These offerings are often placed while intoning Pachamama, Holy Earth, we beg you that your fruitful and generous uterus give us pastures for our llamas. On special communal occasions a llama is sacrificed to the Pachama with the blood of the llama being offered to the Earth, while the animal is consumed as part of a collective ceremonial meal. Veneration of the Pachamama carries over to people´s houses, where sacred stones – usually white quartz rounded by red wool rings – are placed, referencing the protection of the Pachamama.

Given her status as goddess of fertility and the giver of cultivated and wild plants the Pachamama governs the full spectrum of activities associated to Andean agriculture. She is always called upon during seeding and planting. In given cases, an old woman from the community will undertake to perform the role of the Pachamama. Livestock fertility relates directly to the fertility of the people and the land, therefore a pairing of young and beautiful, male and female llamas are chosen as husband and wife, and a ritual marriage between the animals is celebrated. Before a llama caravan sets out the animals are blessed with coa smoke and chicha in a bid to prevent weariness and sickness. In the same ceremony, Pachamama who owns the hills along the way is asked to protect the caravan. Accompanying family members, leave white stones for the Pachamama at the first apacheta they encounter and then return home. The Pachamama is also invoked during water and irrigation ceremonies since she is the mother of the hills and therefore the sources of springs.

Pachamama is perceived as a female goddess with en equally divine husband, a great astral, creator-god. This god takes different names in different regions, such as Pachacamac or Viracocha. But in most places where I have worked in Northwestern Argentina, it is only the Pachamama who is named.

Below the Pachamama are a number of lesser deities that aid her on specific tasks or are masters of particular landforms. For instance, apus or achachilas are the spirits of individual and important mountains – they are represented as elderly men wearing ponchos. Coquena is the shepherd of the vicuña; he cares and herds them, and punishes anyone who kills them. Coquena is depicted as a dwarf dressed in vicuña poncho and garments.

The Pachamama is often a gentle and conciliatory deity but she, locals insist, can also become angry or dissatisfied, expressing these emotions through earthquakes, tremors, and landslides. Abuse of the land, the suffering of animals, and the neglect of plants can make the Pachamama angry, making her lash out and punish those who transgress in her care. Currently in the West there is a powerful metaphor concerning the Mother Earth’s sadness, with the environmental natural disasters we are experiencing interpreted as her revenge for the pain humans have caused her.

There is indeed, only one way to pacify the Pachamama, thereby once again receiving her love and blessings, and that it is to change our attitude towards the Earth, understanding that we are not owners, but rather an aspect within the fold of the Pachamama, at one with her and the rest of the natural world.

References

Aranguren Paz, A. 1975. Las creencias y ritos mágicos religiosos de los pastores puneños. Allpanchis 8-Cusco.

Cipolletti M.S. 1984. Llamas y mulas, treque y venta: el testimonio de un arriero puneño. Revista Andina, 2, 513-538.

Mariscotti de Gorlitz, A.M. 1978. Pachamama, Santa Tierra: Contribución al estudio de la religión autóctona en los Andes centro-meridionales. Indiana. Beiheft Supplement. Ibero-amerikanisches Institut. Mann Verlag. Berlin. Germany.

Profile of Bibiana Vilá

Dr. Bibiana Vilá is Principal Researcher of the National Research Council (CONICET) Argentina and Director of the Vicuñas, Camelids and Environment (VICAM). She has run, a practical and symbolical biodiversity conservation project in the Andean altiplano, northwest Argentina, for more than 30 years. She is a highly accomplished and skilled scientist and wildlife conservationist.

Vicuñas are a wild species of enormous ecological, economic, and socio-cultural importance in South America. Their fine fleece is highly prized, but on the other hand, they were slaughtered in large numbers for centuries. VICAM headed by Dr. Vilá, in consort with local Andean communities, has been very important in recovering an ancient pre-hispanic wildlife capture technique, the chaku, in order to achieve the conservation and sustainable use of vicuñas. Approaches have been developed which will permit the regular capture and shearing and release of wild vicuñas, thus generating income for otherwise economically deprived indigenous communities. This income will also provide important incentives to conserve the species and the ecosystem. VICAM comprises 12 people – with varied profiles covering biological and social sciences – devoted to different aspects of conservation. Its conservation vision blends science-based environmental management and local indigenous knowledge, promoting ecological sustainability rooted in objective scientific data and a respect of local perceptions and practices. This project is truly a model for modern wildlife conservation, and can serve as inspiration for others working in the field.

Dr. Vilá is an accomplished scientist, who regularly publishes her work in high impact academic journals. Also, she works effectively with remote mountain communities under sometimes extremely harsh environmental conditions of cold, dryness, and high winds. As a principal researcher of the CONICET, Dr. Vilá is studying wild vicuñas, and Andean environmental sustainability. She is also a gifted teacher and mentor, and teaches "Environmental Education for rural areas" as part time professor of the Public National University of Luján. In the Ministry of Science of Argentina, she is the scientific coordinator of the Advisory Commission on Biodiversity and Sustainability. She is the representative of the CONICET in the Committee for the Development of Mountainous Regions of Argentina (Mountain Partnership FAO). She is the vice president of Latinoamerican Society of Ethnobiology (SOLAE). She is the national focal point of the Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD).