The Consumption Ecosystem

- James Whitlow Delano

- Photojournalist

Grapes of Wrath's Tom Joad: "Takes no nerve to do something, ain't nothin' else you can do".

Out of sight, out of mind billions labor in poverty so more-prosperous end-consumers can enjoy a bounty of cheap food, cheap energy and cheap goods. By no choice of their own, they must shoulder a heavy burden so that more prosperous end-consumers can live better, more fulfilling lives secure in the belief that the supply of cheap stuff is a birth right not a privilege. The bounty of this capitalistic Mardi Gras, most consumers believe, is supposed to go on forever, free from consequences.

Multinational corporations, just like their colonial predecessors, extract resources and exploit cheap labor, as if the land and those who live on it are completely expendable. The goal to minimize production costs and maximize profit seems to take precedent above all else. With the rise of Asia, new players, including state-owned corporations, have emerged and become the biggest commodity consumer markets. Hard-fought gains in human rights and environmental protection are quickly being erasing.

I have begun to document the export of resource exploitation and heavy industry to Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America by these new players in Asia as they aggressively seek fuel their own economic growth, mitigate their own domestic environmental issues and satisfy their own increasingly demanding consumers. And so the cycle begins again.

What has been lacking in most of the reporting, whether it be celebrating the rise of markets, or cautionary tales about climate change and environmental damage, is establishing the direct connection between the consumer choices in the post-industrial world and the affects they have on the lives of people on the other side of the planet in the developing world, on the supply side of what I have dubbed the “Consumption Ecosystem”.

People created the problem but people are, without a doubt, the single biggest component of the potential solutions. An informed consumer can make intelligent choices in their purchases, avoiding products sourced from unscrupulous suppliers, and thereby apply financial pressure on specific manufacturers to clean up their acts. An informed consumer has the power to improve the lives of families far away by exercising the right to reward the ethical players, while walking away from the bad actors.

Unfortunately, this process of informing the consumer has been hit and miss at best and that is what prompted me to visually connect the consumer with the origins of many of the products that, in their world, simply appear on the shelf in shiny, clean packages, betraying very little about their origins.

***************************************************************************************************************************

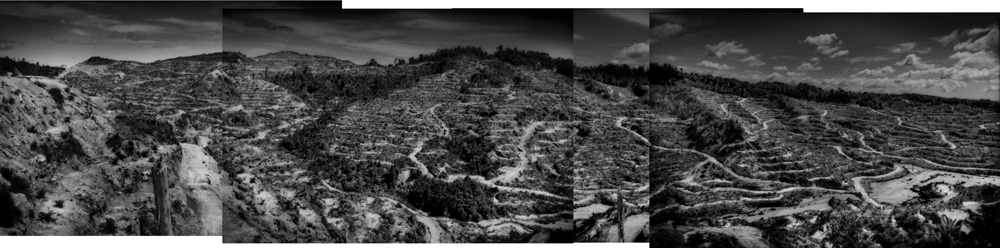

This journey began rather innocently for me in 1994 in Borneo. I was still new to Asia and arrived full of idealism having just read the words of English naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, a contemporary of Darwin who co-developed the theory of natural selection. Wallace wrote this about Borneo in the 1860’s, “For hundreds of miles in every direction a magnificent forest extended over plain and mountain, rock and morass”. Borneo would change little until the 1970’s. Industrial scale logging corporations were quietly, from a global media perspective, spiriting away the resources of powerless, largely voiceless indigenous peoples whose names still identify the mountains, the valleys, and the rivers, by loading mostly unprocessed logs onto waiting ships and exporting the timber for the benefit of others.

Imagine one morning walking into the Tokyo’s Ueno Park only to be denied entry at the gates as heavy equipment can be seen knocking down the beloved Somei-Yoshino cherry trees. You protest, that this is a public park and it belongs to everyone, but a stranger stands in your way waving an official document. Perhaps it has been written in a language you don’t speak, and in an alphabet you cannot read. This park is not yours, explains the stranger. In fact it never was, because it has always belonged to the government who has now leased your land to this corporation you’ve never heard of. Finally, he gleefully informs you, should you try to enter these grounds, he will have you arrested, or worse.

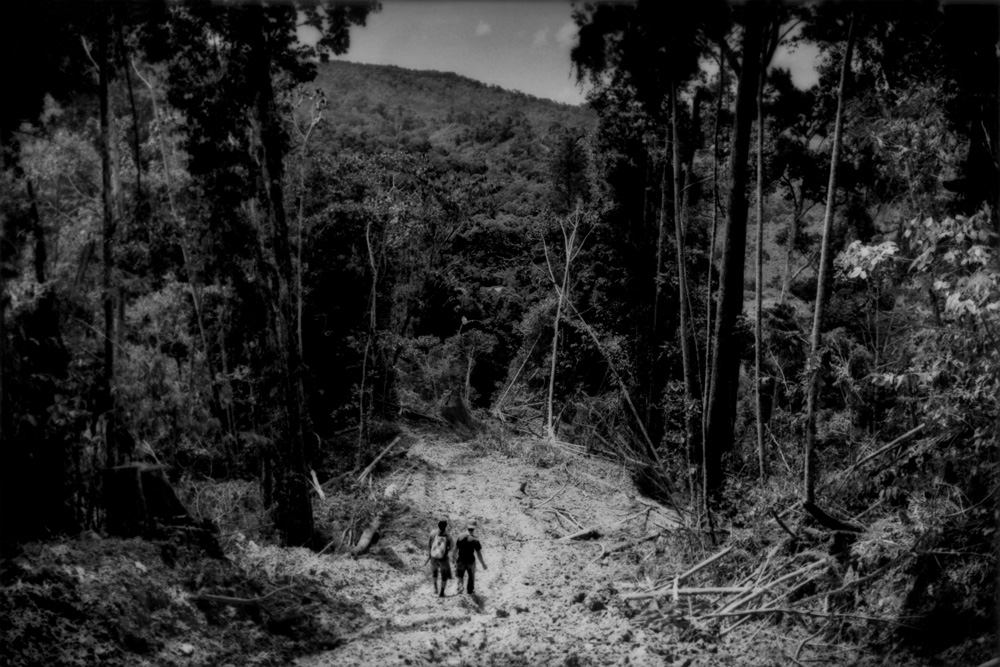

This is exactly the situation I found in Borneo, where indigenous Dayak peoples were no longer able to enter sacred forests where their ancestors had hunted in for a millennium or more because a bureaucrat in an office in a city far away had given over the title to their ancestral homeland to a politically-connected corporation.

I’d flown from Tokyo to Singapore, then on to Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. From Kuching I had boarded a large hydrofoil bound for Sibu. That was where I first sensed a problem. Sawmills lined the banks along the labyrinth of waterways at the mouth of the Rejang River. Smoke spewed from stacks darkened the grey sky. Barges had been roped to landings made up entirely of waste timber. Those trees, which had been felled, were so numerous, apparently of so little value that they were simply used as a foundation for the landing. Cranes were busily lifting hundreds, no, thousands of logs onto this landing and dozens more like it spreading upriver, in the decimated mangrove swamp, where they’d eventually be cut into lumber.

At Sibu, I changed boats, taking a torpedo-like express longboat bound for an outpost called Kapit. There were so many logs floating down the river that the boat would lurch to avoid them in the café latte-colored water. Earlier travelers, even as recently as a decade before my arrival, described dark, tannic but much clearer waters the color of Java tea stained by naturally falling leaves from the great forests. The thin organic tropical top-soil and the inorganic subsoil, exposed by logging, had been swept by the rains into river, completely filling it with silt, a sign that, even given a chance, the forest might not be able to recover, because so much of the organic topsoil washed away.

I arrived deflated in Kapit, as I began to realize that what I had entered did not in any way resemble the most diverse ecosystem in the world, Wallace had described, a natural carbon-sink without equal. I had entered a systemic breakdown of a rainforest ecosystem, a full-blown ecological disaster. Sitting at an outdoor café with an indigenous Iban Dayak man, I ask if it would be possible to see the legendary rainforest in the heart of Borneo from Kapit.

“There is no more virgin forest here”, he said, “you have to go to the Indonesia border to find it and that is a two-day boat ride”. Three years later I would return to Kapit and actually drive with a retired police officer over logging roads to the Indonesia border. He had been right. Loggers had arrived at the Indonesia border. They’d logged every single valley, river course, every mountaintop, that was not protected, from the sea until they could go no further at the international border and surely they would have carried on, if they could have.

Many of the larger logging corporations in Sarawak are quite clever. They own logging companies, sawmills, shipping lines and even newspapers, to control the flow of information. But most clever of all, many have subsidiaries that, once the forest is exhausted, the land is clear-cut and converted to oil palm plantations. Of course, these same corporations own palm oil refineries too, all on land used a generation ago by indigenous peoples for their subsistence. As is the case in much of the world, indigenous people in Sarawak did not possess, at the time loggers first showed up at their doors, title to their own land, as it had simply been known by all around as their customary ancestral land and that was enough.

I have personally visited many Iban longhouse communities. Like the Japanese people, the Iban and all Dayak peoples have wood based cultures. Most Dayaks, their ancestral forest no longer being legally theirs, or displaced by an oil palm plantation, can no longer afford to build their longhouses out of wood. Wood is now too expensive. So, they must construct them using concrete.

The goal of the Consumption Ecosystem project was hatched in Sarawak because I came to realize how little the consumer really knows about the effect our purchases have on people like the Iban. The vast majority of us cannot go through a single day without coming into contact a product containing palm oil and we are not even aware that palm oil is in soaps, shampoo, dish detergent, cosmetics, cooking oil, suntan lotion, shaving cream, biscuits, snack cakes and pies, ice cream, bio fuel, medicines and on and on.

In the past half decade, I have found myself trying to get out in front of these same corporations who, having pretty much exhausted the forests of Malaysia and Indonesia, are actively seeking to replicate this environmental apocalypse in Africa and South America.

Then I discovered other commodities that make our lives richer and more convenient that, out of sight, of mind, corporations were also not acting ethically with local communities or environmentally responsible, from petroleum exploitation in the Amazon to the production of sugar in the Dominican Republic or coffee in Guatemala. In fact, a global pattern started coming into focus where I saw the need to connect the cause and effect dots through photographs.

Then I discovered other commodities that make our lives richer and more convenient that, out of sight, of mind, corporations were also not acting ethically with local communities or environmentally responsible, from petroleum exploitation in the Amazon to the production of sugar in the Dominican Republic or coffee in Guatemala. In fact, a global pattern started coming into focus where I saw the need to connect the cause and effect dots through photographs.

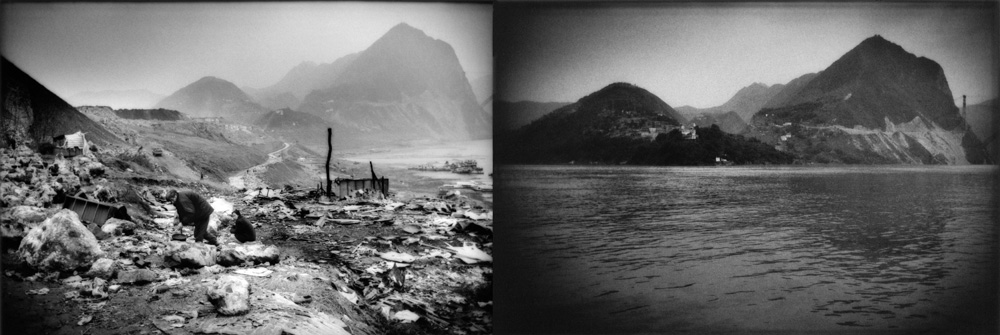

The air, and water in China are fouled to manufacture cheap consumer and high tech goods like smart phones and televisions at higher profits but it is local communities who often pay with their health to make this possible. Migrant workers leave their families behind to undertake perilous migrations to the United States and European Union nations in the hope of raising their families out of poverty. Workers are injured, sometimes losing a limb and are no longer able to work,

plunging loved ones, who depend on them, into uncompensated destitution.

All these issues, I noticed, were being portrayed in the global media as if separate and unrelated. What this collection of photographs attempts to do is bring them together as related parts of the same ecosystem which is designed to enrich the lives of the fortunate consumer at the expense of the impoverished laborer who produces those products, or communities that just happen to sit on top of high-value land. Hopefully a conversation can begin that will make us think about creating a more ethical consumption ecosystem but, in order to do that, first we need to look honestly at the problem.

Photographs by James Whitlow Delano

Profile of James Whitlow Delano

James Whitlow Delano is a documentary storyteller and collector of visual evidence who has lived in Asia for over 2 decades. His work has been awarded internationally: the Alfred Eisenstadt Award (from Columbia University and Life Magazine), Leica’s Oskar Barnack, Picture of the Year International, NPPA Best of Photojournalism, PDN and others for work from China, Japan, Afghanistan and Burma (Myanmar), etc.. His first monograph book, Empire: Impressions from China and work from Japan Mangaland have shown at several Leica Galleries in Europe. Empire was the first ever one-person show of photography at La Triennale di Milano Museum of Art. The Mercy Project / Inochi his charity photo book for hospice received the PX3 Gold Award and the Award of Excellence from Communication Arts. His work has appeared in magazines and photo festivals on five continents from Visa Pour L’Image, Rencontres D’Arles; to Noorderlicht, including their “Sweet and Sour Story of Sugar” project. His latest monograph book, Black Tsunami: Japan 2011 (Foto Evidence), documenting the Japan tsunami and nuclear crisis, was released in 2013. Delano is a grantee for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and received the 2014 Festival Photo Reporter in Saint-Brieuc, France grant for work documenting the destruction of equatorial rainforests and human rights violations of indigenous inhabitants living there. In 2015, Delano founded of Everyday Climate Change Instagram feed, where photographers from 6 continents document global climate change.

Website

http://www.jameswhitlowdelano.com

New Stories:

http://jameswhitlowdelano.photoshelter.com/

Facebook:

http://www.facebook.com/james.whitlow.delano

Twitter:

@jameswdelano

Instagram:

@jameswhitlowdelano