Biodiversity and Climate Change

Alfred A. Oteng-Yeboah

Department of Botany, College of Basic and Applied Sciences, University of Ghana, LEGON, Ghana

Chair, Ghana National Biodiversity Committee

The MIDORI Prize for Biodiversity 2014 Prize Winner

Abstract

The interrelationships between biodiversity and climate change has been explored. In this exploration, it is being established that biodiversity sits at the nexus among the three Rio conventions of UNCCD (Land degradation), UNCBD (Biodiversity) and UNFCCC (Climate change, and that through conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, solutions can be found for land degradation and climate change.

Introduction

In this discourse, a number of questions are being asked and answers provided. It is believed that the answers will educate people on the basic question of the interrelationships between biodiversity and climate change.

What is the common expression among biodiversity and climate scientists these days?

The common expression on biodiversity is that it is being lost at alarming proportions, making it impossible to completely have a clear global or regional picture, in terms of the total numbers of species, their assemblages within and across ecosystems and be able to assess the nature of their habitats where they live and the functions they perform.

On climate change, the common expression is that it is real and countries are experiencing either gradual or rapid changes in the weather patterns they are used to, with episodes of extreme temperature surges contributing to heavy rainfalls, drought and other unusual environmental changes and thus affecting sustainable development and human wellbeing. The latest observation that 2015 could be the hottest year ever recorded and the fact that the Pacific Ocean is becoming a cauldron should make people sit up.

The globe as seen from Apollo 17 (1972)

Why are they making these expressions?

As science informs policy so it is the duty of scientists, including biodiversity and climate scientists, to inform and educate the society about the social, economic and environmental consequences about biodiversity loss and effects of climate change as issues that are inimical to human wellbeing. In so doing they contribute to the promotion of good life. The understanding is that policy and decision makers are made fully aware to engage and develop policies, which may include plans, programmes and projects to reduce the incidences of biodiversity loss and the effects of climate change on biodiversity and ecosystems or completely remove the source of the problem.

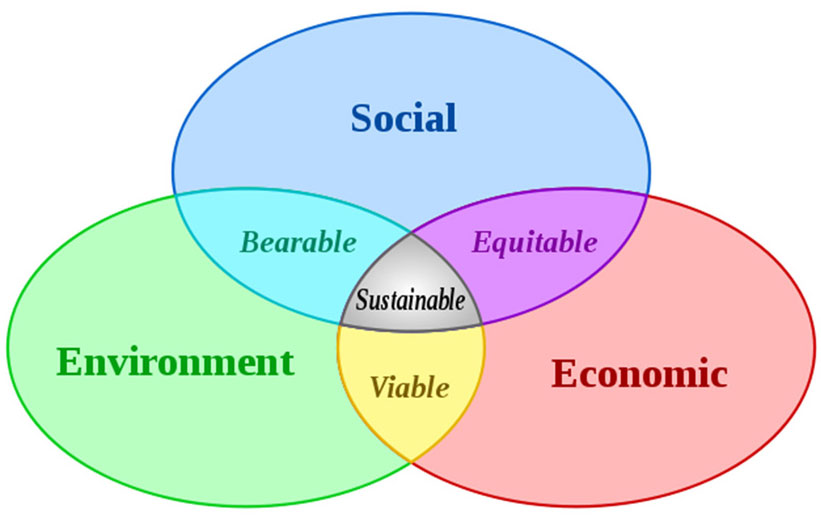

The Sustainable Development Model

How are ordinary people and governments responding to these expressions?

The responses of the ordinary people to these phenomena are swift but that of governments are slow. The ordinary people get affected quickly because their sustenance is hinged on the benefits they derive from the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Climate change appearance alters everything and their aspirations are lost. By ordinary people it includes those whose livelihoods depend solely on what they can eke out from the immediate environment and support themselves from the genetic resources around them for food, fuel, health and finances. The lives of many of such people become pitiable as they are not able to make ends meet because of crop failure which resulted from drought, emergence of pests and diseases and lack of appropriate labour force from climate effects.

Governments’ responses are slow, except in emergency natural situations such as earthquakes, tsunamis, fire, flooding etc., because of several factors including lack of coordination within the extension services and absence of good surveillance teams in monitoring and evaluation. At the time of government action, a lot of damage may have been done. It is usually at this stage that governments wake up and call for international action. This begins the processes of intergovernmental cooperation.

Chronology of government actions on problems of biodiversity and climate change

From 1987 to the present, governments of the world have engaged with one another to find solutions to the world’s developmental issues such as poverty, extreme hunger, child mortality, maternal health, and environmental degradation, which have resulted from biodiversity. ‘Our common Future’ was an outcome in 1989 which also led to the development of the Agenda 21 principles of sustainable development. The UN Conference on Environment and Development in June 1992 culminated in the signing of 3 conventions, which are usually referred to as The Rio conventions of UNCCD, UNCBD and the UNFCCC to promote environmental aspects of agenda 21 in the areas of land degradation, biodiversity and climate change respectively. While each convention had Parties and organized COPs, IPCC was already in place providing timely scientific advice on carbon and other greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions that had been identified as responsible for global warming. At long last the reasons for climate change effects were understood and governments were advised to cut down on their emissions of these gases. How to cut the carbon and other GHGs emissions has engaged governments and there has been series of negotiations. The most developed country Parties whose industries generate more of these gases have been targeted to reduce their emissions (Kyoto Protocol). The Kyoto Protocol is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which commits its Parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets. Recognizing that developed countries are principally responsible for the current high levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the atmosphere as a result of more than 150 years of industrial activity, the Protocol places a heavier burden on developed nations under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.” The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Kyoto, Japan, on 11 December 1997 and entered into force on 16 February 2005. The detailed rules for the implementation of the Protocol were adopted at COP 7 in Marrakesh, Morocco, in 2001, and are referred to as the “Marrakesh Accords.” Its first commitment period started in 2008 and ended in 2012. The Doha accord in 2012 brought New commitments for Annex I Parties to the Kyoto Protocol who agreed to take on commitments in a second commitment period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2020; A revised list of greenhouse gases (GHG) to be reported on by Parties in the second commitment period; and Amendments to several articles of the Kyoto Protocol which specifically referenced issues pertaining to the first commitment period and which needed to be updated for the second commitment period.

For developing country Parties whose carbon stocks in the form of forests are being cut and thus reducing natural carbon sinks, sometimes indiscriminately for other land-uses, have also been requested for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) with the appropriate plans and programmes in reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries (REDD+).

A pristine primaty forest vegatation in Ghana

Courtesy of Nick Hodgetts 2014 from the Atewa Forest, Ghana to Alfred Oteng-Yaboah

Through government efforts, the issues of climate change and biodiversity loss have been firmly linked. United Nations sponsored intergovernmental meetings of World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) whose plan of actions included the introduction of the Millennium development Goals (MDGs) to commemorate Rio+10, set global agenda to deal with the threat of climate change and biodiversity loss. The recent global assembly in Rio de Janeiro in 2012, dubbed Rio+20 rehashed agenda 21 ideals and recapped it as ‘the Future we want’ in which solutions to climate change effects and biodiversity loss could be found, with special attention to an evaluation of the MDGs as a new post 2015 development agenda loomed ahead. In time and towards the end of September 2015, the new 17 goal global agenda was agreed by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) to operate from January 2016. This is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) whose focus have been hinged on human wellbeing, bringing to mind the need to ensure a balance among human behavior (social), human actions for survival (economy) and human interactions with the environment (which includes the biophysical components, especially biodiversity, that promote ecosystem renewal, resuscitation and resilience for service).

Sustainable Development Goals

SOURCE: UN DESA

© United Nation Department of Economic and Social Affairs

From biodiversity viewpoint, tremendous efforts have been made in terms of an agreed biodiversity strategy of 2011-2020 and the Aichi Targets CBD 2014). The Aichi targets are 20 and each one of them is expected to be achieved by 2020 towards a global vision of halting biodiversity loss by 2050. An assessment of the current extent of biodiversity loss has been lacking. The engagement of governments, supported by civil society organizations, to birth IPBES in 2012 as a biodiversity platform for assessments, utilizing available information and supporting the biodiversity related agreements has been remarkable. IPBES’s 4 key functions are to Facilitate access to the scientific information needs of policymakers, promoting and facilitating the generation of new knowledge where this is necessary; to Deliver global, regional, sub-regional and thematic assessments as requested, and at the same time promote and facilitate assessments at the national level; to Promote the development and use of policy support tools and methodologies so that the results of assessments can be more effectively applied; and to Identify and prioritize capacity building needs for improving the science-policy interface at appropriate levels, and provide, call for and facilitate access to the necessary resources for addressing the highest priority needs directly relating to its activities. (UNEP/IPBES MI/2/9).

What is so special about these two phenomena?

Biodiversity is seen in the form of species whose individuals form populations, live in habitats and constitute part of the ecosystem and which taxonomically aggregate into genera and families of plants, animals and other living organisms. The basic component of these individuals is the genetic composition. It is this that makes up the genetic resources which are used for food and agriculture. These play crucial roles in food security, nutrition and livelihoods and in the provision of environmental services. They are the key components of sustainability, resilience and adaptability in production systems. They underpin the ability of crops, livestock, aquatic organisms and forest trees to withstand a range of harsh conditions. Thanks to their genetic diversity, plants, animals and micro-organisms adapt and survive when their environments change (FAO, 2015). Thus Climate change poses new challenges to the management of the world’s genetic resources for food and agriculture, but it also underlines their importance.

How do we understand these two phenomena?

There is a nexus that operates among biodiversity, climate change and land and/or water degradation. Because of the components of sustainability, resilience and adaptability in production systems, they underpin the ability of crops, livestock, aquatic organisms and forest trees to withstand a range of harsh conditions. Thus land degradation which results from climate change or from human activities can be rehabilitated through conservation. The concept of adaptation (Bedmar et al 2015) as a means of countering climate change effects on an ecosystem depends largely on the presence of biodiversity. The concept of Climate-smart-agriculture(CSA) basically recalls biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.

Are there any contributions that individuals can make?

The issue of biodiversity loss and climate change is an issue for everybody. Climate change has been found to and will cause shifts in the distribution of land areas suitable for the cultivation of a wide range of crops. Studies indicate a general trend towards the loss of cropping areas especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Climate change is also known to affect and indeed affects ecosystem dynamics in various ways. The Potential consequences are seen to include asynchrony between crop flowering and the presence of pollinators, and the spread of favourable conditions for invasive alien species, pests and parasites. Consequently, as ecosystems change, the distribution and abundance of disease vectors are also likely to be affected, with consequences for the epidemiology of many crop and livestock diseases (FAO, 2015).

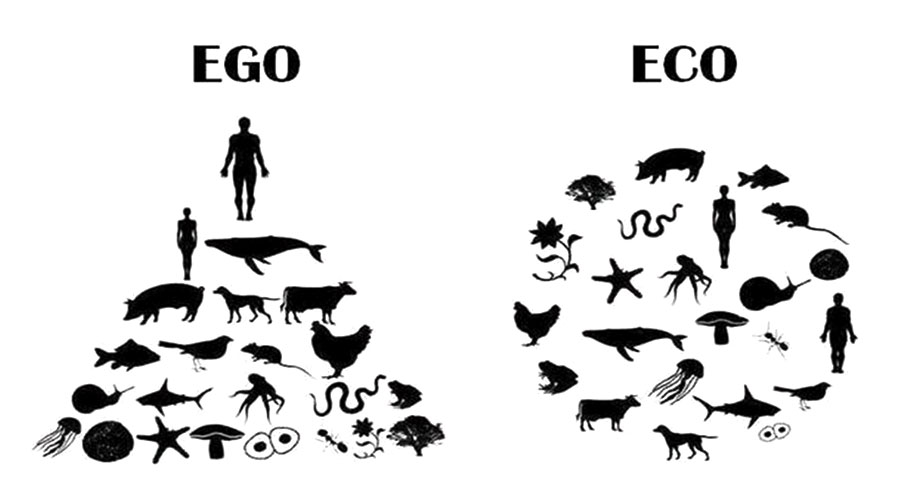

The answers is from MAN

REFERENCES

adaptation planning: an analysis of the National Adaptation Programmes of Action. CCAFS Working Paper no. 95. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Copenhagen, Denmark. Available online at: www.ccafs.cgiar.org

CBD. 2014. Global Biodiversity Outlook 4 — Summary and Conclusions. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Montréal, 20 pages

FAO. 2015. Coping with climate change – the roles of genetic resources for food and agriculture. Rome

Profile of Alfred Oteng-Yeboah

As an advocate for biodiversity policy at the global level, Dr. Alfred Oteng-Yeboah has contributed to the establishment of global mechanisms to raise the profile of biodiversity on the global political scene. He has co-chaired the Executive Committee of the International Mechanism of Scientific Expertise on Biodiversity (IMoSEB) and played an active role during the global consultation process towards establishment of a science-policy interface for biodiversity and ecosystem services since 2005. Consequently he participated in the founding of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and acted as a member of an initial international planning committee for UNEP towards the first, second and third meetings for IPBES, co-chaired the first two meetings and acted as the vice-chair for the third. He reviewed the work of IPBES at the eighth session of the Open Working Group of the United Nations General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals in New York on 3 February 2014, and presented and defended the idea of having a goal on ‘life supporting systems.’

As the chair of the 9th and 10th Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA), he successfully steered the Subsidiary Body and the Convention towards the consideration of specific targets and goals as strategies to achieve a substantial reduction in the loss of global biodiversity by 2010. He chaired many contact groups at SBSTTA and COPs including those on Biofuels, Sustainable Use with the SATOYAMA Initiative, Forests, Marine Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, the Global Taxonomy Initiative, Capacity Building, and Protected Areas. As Vice-Chair for the Standing Committee of Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species (CITES), Dr. Oteng-Yeboah chaired a group to draft a strategic vision which was adopted by the Standing Committee at its 54th meeting. As a member of the Scientific Council for the UN Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), he spoke on behalf of Africa and stressed the need for scientific advice to secure the migratory routes. He also served as a member of the International Advisory Committee for UNESCO Biosphere Reserves for a three-year assignment, and provided support for the revision of the establishment of new Biosphere Reserves. As a board member of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), he contributed to the production of the assessment report on the world’s ecosystem resources. His contributions to biodiversity related international mechanisms are enormous. Currently he is supporting the promotion of sustainable use of biodiversity through serving as Chair of the Ghana National Biodiversity Committee and Chair of the Steering Committee of the International Partnership on the SATOYAMA Initiative (IPSI).

Dr. Oteng-Yeboah, who has played a role of interface between science and policy, has been giving strong impacts not only to young Africans but also to people from other parts of the world, and especially to the beginners of international negotiations on biodiversity.